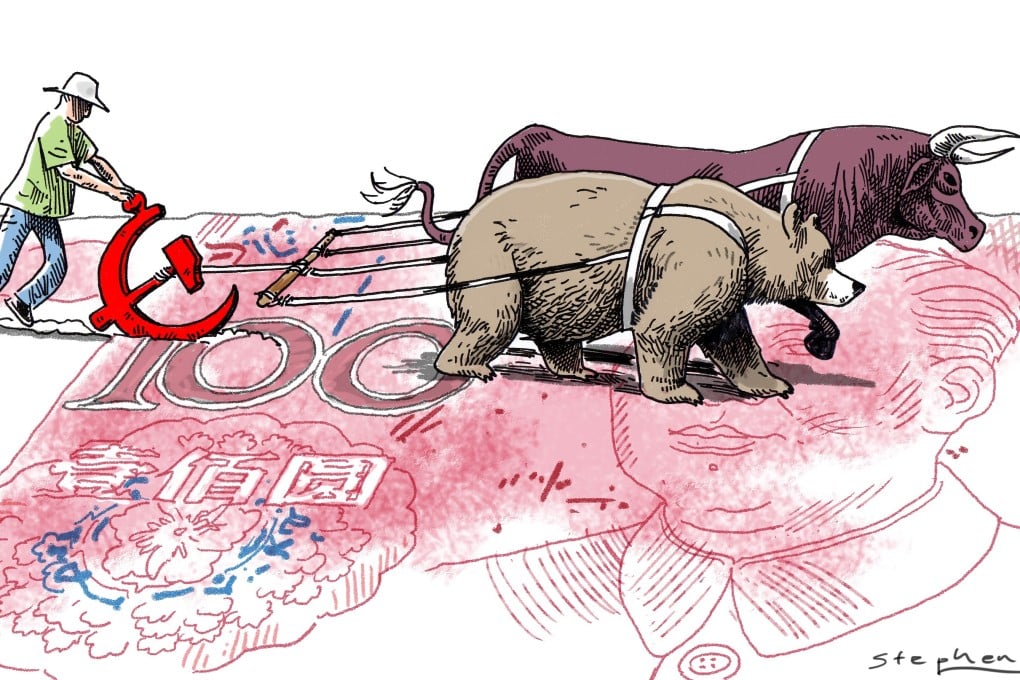

Why Tiananmen Square’s real legacy may be Communist Party unity and the success of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms

- After June 4, the purge of liberals who wanted political reform may have given Deng Xiaoping the space he needed to keep economic reforms going when the communist bloc collapsed

Sometime around June 4, 1989, rumours circulated that Deng Xiaoping had said that 200 lives were a small price for China to pay for 20 years of stability. While China clearly did not gain 20 years of stability, the case can be made that, in retrospect, by allowing the purge of the entire liberal wing of the Communist Party, June 4 brought “great unity” to that leadership, which has facilitated China’s rise to great-power status.

The decade of the 1980s was intellectually vibrant. China was deeply engrossed in searching for a pathway forward from Maoism to markets, but there were no successful models to follow. Moreover, the leadership was polarised – less so in the early 1980s but, by 1986, sharp contradictions split the leadership.

While the former group emphasised “opening and reform”, the latter clung to Deng’s “four cardinal principles”, the most important being the dominance of the Communist Party and the “socialist road”.

The struggles between the two factions became more complex after college students became active participants in the politics of reform. In the late autumn of 1986, reformers in the Central Party Propaganda Department encouraged students and factory managers to discuss the salience of political reform.